1. Scale of Lobbying in the U.S.

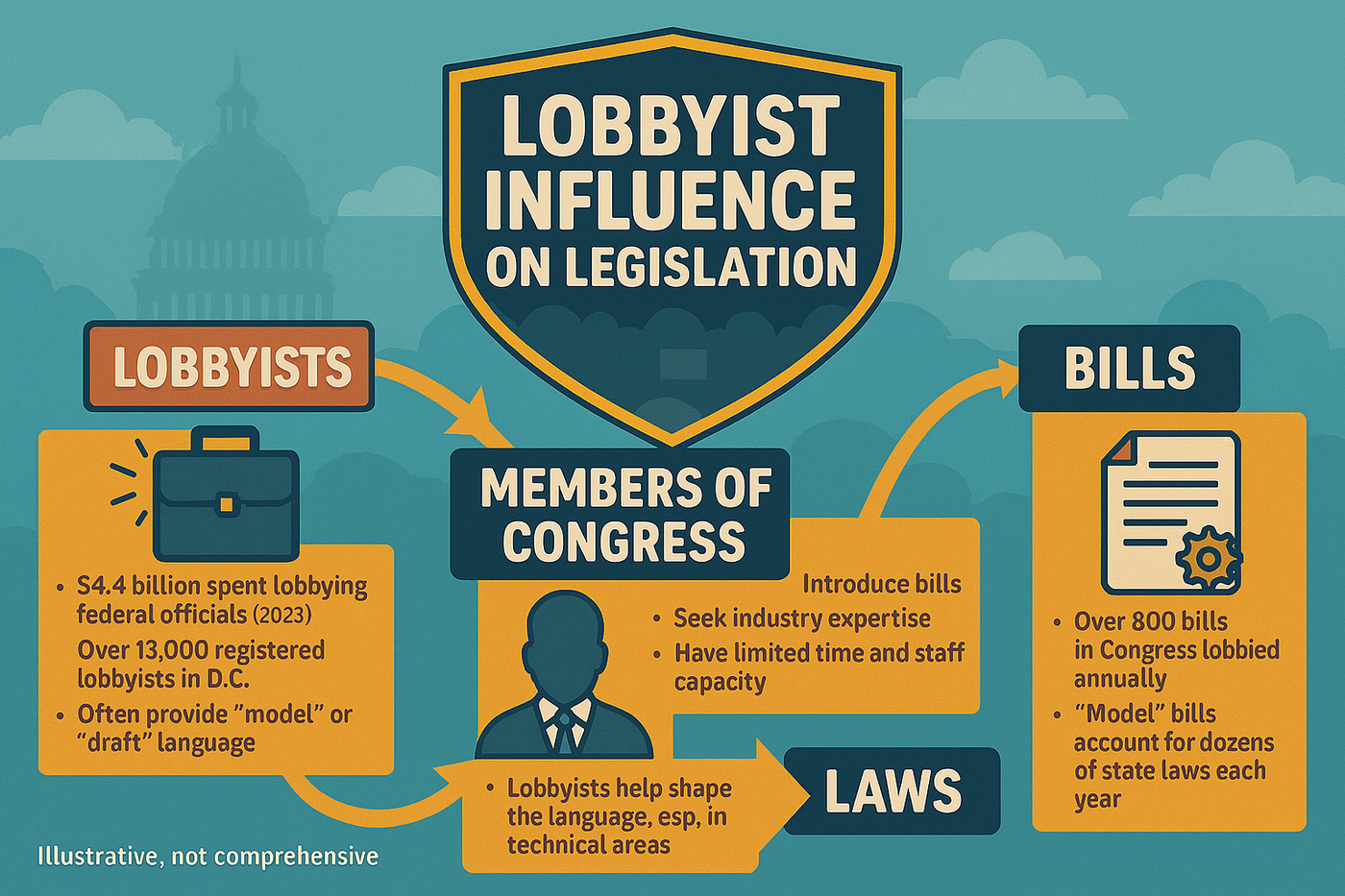

- The Scale of Lobbying in the U.S. In 2024, lobbying expenditures reached $4.44 billion, with more than 13,000 registered lobbyists outnumbering members of Congress by a ratio of 20 to 1. This significant financial and personnel advantage allows lobbyists to exert considerable influence on the legislative process, potentially skewing policy outcomes in favor of their clients.

- Bills with Lobbying Activity: In 2025, 842 federal bills had documented lobbying activity, averaging $7.1 million per lawmaker in lobbying influence.

https://lobbyit.com/lobbyists-interest-groups-and-power/

2. How Often Do Lobbyists Draft Bills?

- Direct Drafting: It is common for lobbyists to draft entire bills or major sections, especially in technical areas such as finance, energy, and healthcare.

- Example: A House bill to roll back Dodd-Frank reforms contained 70 of 85 lines drafted by Citigroup lobbyists.

- Model Legislation:

- A USA TODAY investigation found 10,000 bills introduced nationwide over eight years were nearly identical to model bills from special interest groups; 2,100 became law.

- ALEC alone accounts for ~200 model bills becoming Law annually at the state level.

3. Why Does This Happen?

- Staff Constraints: Congressional offices have small teams (often <20 staff members) handling thousands of bills, making them reliant on external expertise.

- Complexity: Technical sectors (banking, telecom, energy) require specialized knowledge that lobbyists provide.

- Fundraising Pressure: Lawmakers devote a significant amount of time to campaign fundraising, reducing their time for drafting legislation.

4. Influence Patterns

- Industry Concentration: Healthcare, technology, defense, energy, and finance sectors dominate lobbying expenditures. Each of these industries has its own set of policy priorities and can utilize its financial resources to advocate for legislation that benefits its bottom line, potentially at the expense of broader societal interests.

- Copy-Paste Legislation: State legislatures are particularly vulnerable to “copycat bills” from ALEC and similar groups.

5. Oversight and TransparencyThe

- Lobbying Disclosure Act (LDA) requires the reporting of lobbying activities but does not mandate the disclosure of who wrote the bill language.

- GAO audits demonstrate compliance with disclosure filings, but there is no mechanism to track the authorship of legislative text.

Key Takeaways

- Lobbyists routinely draft legislative language, especially in specialized policy areas.

- Model bills from organizations such as ALEC have shaped thousands of state laws and some federal proposals.

- A lack of authorship transparency means that the extent of lobbyist influence is underreported.

Policy Reform Ideas

- Authorship Disclosure: Require bills to list all external contributors.

- Expand CRS & GAO Oversight: Increase congressional capacity to reduce reliance on lobbyists.

- Public Database of Model Bills: Track and flag copy-paste legislation.

6. Google search on Washington, DC Lobbying

In Washington, D.C., “special interest lobbyists” are individuals or firms hired by organizations to influence public policy and legislation on specific issues. They represent a diverse range of clients, including major corporations, industry associations, non-profits, and smaller advocacy groups.

Types of special interests

Special interest groups lobbying in D.C. represent virtually every sector of American life and the economy, including:

Industry and corporate interests: Large corporations across sectors such as finance, defense, technology, healthcare, and energy are among the largest spenders on lobbying.

- Trade associations: These groups represent the collective interests of multiple companies within a single industry. Examples include the American Petroleum Institute or the American Farm Bureau.

- Labor unions: Organizations that advocate for the rights and interests of workers often employ lobbyists to influence labor laws and regulations.

- Nonprofits and public interest groups: These organizations lobby on behalf of specific causes or social issues, such as environmental protection, healthcare funding, or human rights.

- Foreign governments: Some foreign governments retain lobbying firms in Washington, D.C., to advance their interests within the U.S. government.

The lobbying process

The activities of special interest lobbyists generally include:

Providing information to lawmakers: Lobbyists often serve as subject-matter experts, offering data, research, and analysis to members of Congress and their staff.

- Building relationships: A key part of the job is building long-term professional relationships with policymakers and their staff.

- Drafting legislation: Lobbyists may assist in drafting or proposing specific legislative language that favors their clients’ interests.

- Organizing grassroots campaigns: Some campaigns involve mobilizing large numbers of people to contact their elected officials to advocate for a specific policy.

- Making campaign contributions: Many special interest groups use political action committees (PACs) to make financial contributions to political campaigns, a practice often intertwined with lobbying.

Key players and trends

Top firms: According to Bloomberg Government reports, the top-earning lobbying firms in 2022 included Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck, Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld, and Holland & Knight.

- The “revolving door”: A common and controversial practice in Washington, D.C., is the “revolving door,” in which individuals move between government service and lucrative lobbying positions. In 2025, the Campaign Legal Center reported that the Trump administration had abandoned rules that limited this practice, raising concerns about conflicts of interest.

- Lobbying Disclosure: The 1995 Lobbying Disclosure Act requires lobbyists to register and file quarterly reports detailing their lobbying activities, clients, and the issues they are lobbying on. However, critics argue that many activities go unreported.

- Growth of smaller firms: While large, well-funded “K Street” firms remain influential, newer, more accessible lobbying firms, such as Lobbyit.com, have emerged to serve smaller organizations with more modest budgets.